Happy Independence Day...According to John Adams

Happy Independence Day! Or at least that’s what today would have been if John Adams, founding father and second president, had his way. So why the mix-up? To answer that, let’s go back to July 1776 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In the summer of 1776, the Second Continental Congress had convened in Philadelphia in order to decide the fate of the Thirteen Colonies. In fact it was on July 2, 1776 that the assembled delegates voted to officially declare independence from Great Britain. The vote had originally been delayed from June 7, as a few states still felt apprehensive about voting in favor of independence. In fact, at this previous session it was decided that an official document declaring American independence would be drafted. Thomas Jefferson was selected to author the document, which would eventually come to be as the Declaration of Independence we know today.

Around a month later, the delegates gathered once again and voted unanimously to adopt the resolution formally declaring independence. This resolution, which had been originally submitted by Virginian delegate Richard Henry Lee, read as follows:

“That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

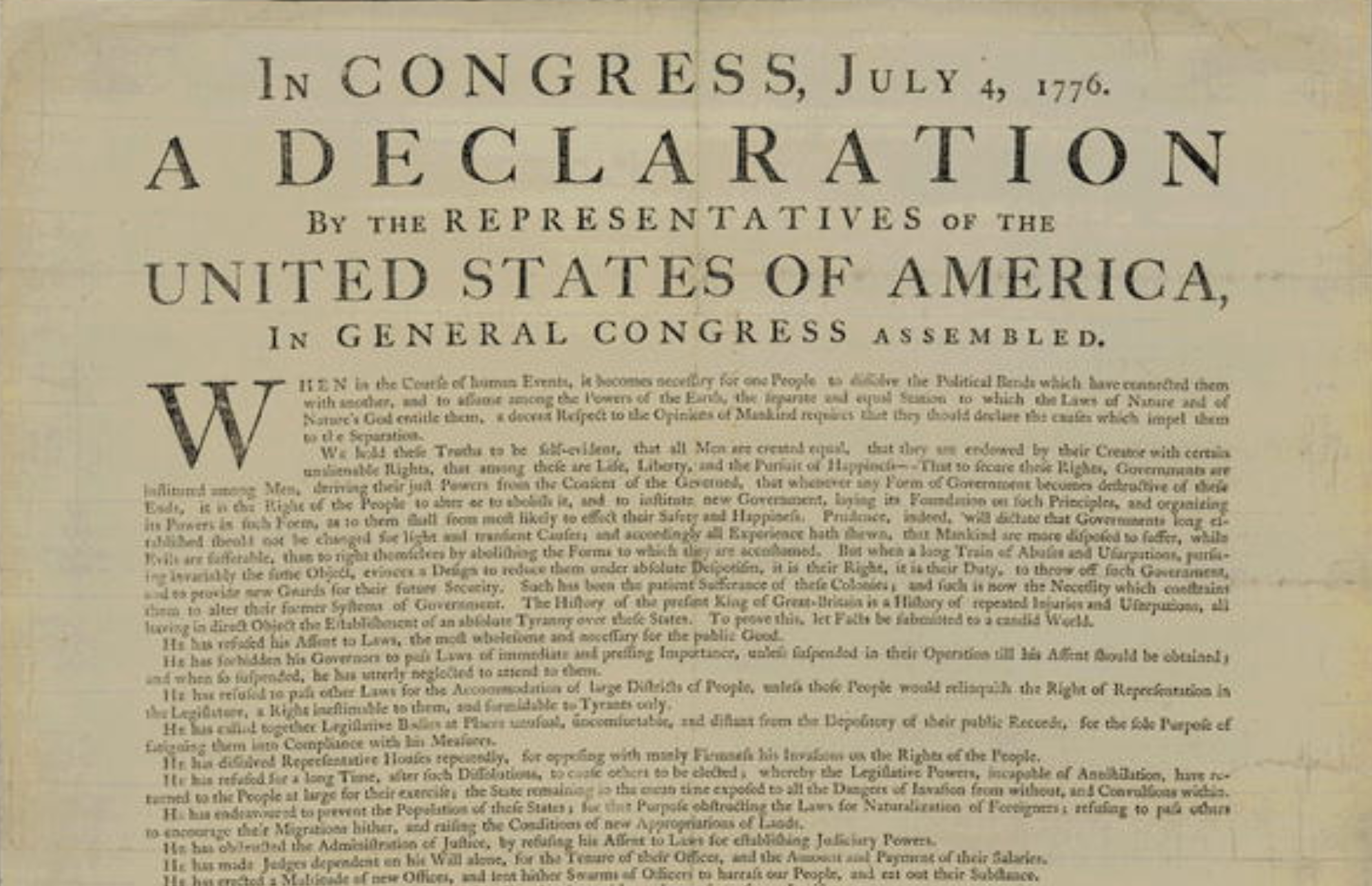

So if the founding fathers officially voted to declare their independence on July 2, then why do we officially celebrate on July 4? That’s because July 4, 1776 is when the final draft of the Declaration of Independence — the one we know and love today — was officially approved by the delegates of the Second Continental Congress. In fact, this is the reason why “IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776” is written at the very top of the document. As to why the delegates didn’t vote on the Declaration of Independence on the same day they approved the Lee Resolution: it took those two days in order to debate over and approve the final edits to the document before a final draft was created. To further complicate things, although the official text of the Declaration of Independence was approved on July 4, the document itself would not be officially signed until August 2, 1776. Even then, not every delegate who had been present at the early July session was able to return to officially add their signature to the document.

The date, July 4, 1776, at the top of the Declaration of Independence signifies the date it was officially ratified by the Second Continental Congress. Pictured here is a copy of the document’s text printed after its ratification but before it was signed in order for distribution to the American public.

Right after the official declaration of American independence, the founding fathers did not see to consider the concept of a holiday to celebrate the occasion until seemingly around a year or so later. That makes sense though, considering they had to fight Britain in all its military might if they wanted to successfully achieve full independence. However, immediately after the official vote for independence was cast — John Adams hailed July 2, 1776 as a day that would go down in history. The very next day, he wrote in a letter to his wife, Abigail Adams, the following:

“The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

Unfortunately, when July 2, 1777 came around — none of the delegates who had been present at that historic session in Philadelphia the previous year even realized it until the following day. Having finally recalled the event, it made sense to celebrate the anniversary of American independence on July 4. This is according to historian Pauline Maier in her book American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Maier also details that celebrations of Independence Day as a holiday did not officially begin for quite some time after. This can be attributed to the political rivalry between Federalist John Adams and Republican Thomas Jefferson. So can we really attribute the date on which we celebrate Independence Day to forgetfulness and rivals being petty? Maybe it’s more likely than we think.

Regardless, Jefferson had his own words to say about the holiday:

“For ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them. ”

In another display of how surreal human history can truly be, both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson passed away on the same day. That day also happened to be the 50th anniversary of American independence, at least to Jefferson: July 4, 1826.

Related Content From Historic America:

Audio Tour: Founding Fathers’ Footsteps

Journal: Philadelphia Summers and the U.S. Constitution

Journal: Carpenter’s Hall

Podcast: Keep an eye out for our upcoming series on Revolutionary War Philadelphia!