A Conversation with Jake Wynn of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum

Clara Barton, photo provided by the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum website.

Clara Barton is one of the most important women in American history. While Barton is well remembered today for being the founder of the American Red Cross, her career was as lengthy as it was impressive. Having worked as a teacher as well as being one of the first women to work for the federal government, Clara Barton became a relief worker at the outbreak of the Civil War. We decided to speak with Jake Wynn, Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum, about her work and legacy.

Jake Wynn graduated from Hood College with a degree in History and Communication Arts. He has previously worked with the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, the Tourism Council of Frederick County, and the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area. Jake’s historic interests include the towns of William Valley, the small Pennsylvania community in which he grew up, the medical practices of the Civil War era, and the experiences of the Civil War soldiers. Read our conversation with him below!

Sonali: Clara Barton’s bravery as a combat nurse changed the way that women were seen on the battlefield. What was her role in the Civil War and how did she begin to change this perspective of women?

Jake: Her work during the war, especially the nursing side, is something that she never had any intention of doing. She didn’t have any pre-knowledge that this was going to occur or that she would become a nurse and that she would be having those responsibilities, let alone be on a battlefield. Everything was ad hoc, makeshift, and she was kind of stumbling around into it. She's living in Washington DC when the war broke out and was trying to get the job at the U.S. Patent Office that she previously lost as a result of anti-women beliefs. In the 1850’s she had worked at the patent office briefly before getting fired and she gets her job back, so she dealt with inequality especially for women all through her life whether as a teacher back in Massachusetts or in the federal workforce in the 1850s and so on. Surprisingly, she runs into it again when she starts doing work during the Civil War even as a relief worker.

I think one of the big elements when talking about Barton and the Civil War is that we do kind of silo her as a nurse, but the nursing side of her work is actually a pretty tiny fragment of what she does during the Civil War. She is really a humanitarian and relief worker gathering supplies and delivering those supplies as well as supporting the mental, physical, and emotional health of the Union soldiers at the front lines and that really takes up the lion share of her work that she starts in 1861 and carries through the end of the war. She does have those very high profile nursing experiences; like what she does in Virginia in 1862, then at Antietam in Maryland during September of 1862, and down in South Carolina among free people in 1863. It's kind of a mix of this nursing experience working with wounded and sick soldiers and also with refugee populations as well, but also doing this relief work.

The U.S. Patent Office around the time Clara Barton would have been employed there. Learn more about her time as a woman employed by the federal government as well as the gender discrimination she faced on the Missing Soldiers Museum’s website

Sonali: Continued question - In terms of mental health, in what ways did she step in to take care of soldiers during this physically draining war?

Jake: Two points - how she cared for others. She never has children, she never marries, but she takes on this motherly role among the soldiers she serves with because she’s a bit older. This is a misconception that I had when I started working closely with Barton and her story is that she’s almost 40 years old when the war breaks out. The average life expectancy for American women in those days was in the early 50s, so she’s actually getting well into middle age. When she's in the hospital, she actually writes about this but she is being mistaken for soldiers mothers who may be dying from wounds or may be very ill. She has a comforting presence that is really helpful in that kind of mental and emotional side. She becomes very close friends with some of the soldiers that she serves with. To flip over to Barton’s side, she is a person who often struggles with her own mental health issues throughout her life. There is a vein of depression that runs through her family history and she has family members who were institutionalized. Barton in the 1870s, after the war, spent time at a sanitarium for mental health issues in New York State. During the Civil War one of the ways, of course before medication and before we have this modern understanding of mental illness and depression, she found a way to balance herself by throwing her self into her work. So in a weird way, by helping others she is helping herself and she's able to find balance by throwing herself into this work. There's a lot of looking back and diagnosing what mental illnesses she may have had. She was formally diagnosed with melancholia, which is the 19th century term for depression, and there's some speculation that she may have had bipolar disorder. It's interesting to see that helping others seems to be the way that she really found that balance that she needed in life to be able to move forward and when she doesn't have that there are times where she considers suicide where she is at the verge of death just because it brings herself so low when she doesn’t have that balance.

Sonali: Clearly, Clara Barton was known for her service, so much so that she was given the nickname "Angel of the Battlefield." How did this nickname come about?

Monument to Clara Barton at the Antietam National Battlefield. The red cross on this monument was formed using bricks from the home in which she was born.

Jake: That's one of the great Barton stories and one that she tells and retells often. In September 1862 the Confederate Army invades Maryland, the Union Army pursues, Barton accompanies the United States Army with three wagons that she loaded up full of supplies and goes to the battlefield. As the Battle of Antietam breaks out she is very close by, shows up at a field hospital and unloads her supplies and jumps right into the action. She is nursing, she is bringing her supplies to a hospital and even though this is at 8 or 9 o’ clock in the morning of the battle she is already running out of supplies. It's likely the hospital that she’s at is one of the busiest of any on that battlefield, in the bloodiest day in American history. This is a truly unprecedented kind of situation that she's stepping into and she runs into this Army surgeon from Pennsylvania that she had actually been with on previous battlefield journeys with. You can imagine how startled he would have been to see this woman who had showed up previously to field hospitals where he was at. She jumps in and she's there for about 72 hours until her supplies are exhausted and she herself is exhausted then she goes back home. This surgeon, a guy named James Dunn ,writes a letter to his wife after the battle and describes running into to Miss Barton, as he calls her, and describes her as being the “Angel of the Battlefield.” He also throws some shade at General McClellan, the commander of the army, and says that he sinks beneath Clara Barton, who is the true hero. Barton herself talks about this in speeches after the war as she relays a story of giving a soldier a drink of water in this hospital, when a bullet went through the sleeve of her dress and actually struck the soldier she was working on in the chest and killed him instantly in her arms. That story has been told and retold and I do think that it's a good place to mention that in Barton's post-war speeches, the tales become longer and longer and further and further from the truth. She tells some tall tales in the aftermath of the war, so it's always good to find a second source for anything that Barton says. After the war, she was trying to raise money and awareness for her causes, so she didn't feel like she needed to be constrained by the facts in doing that.

Sonali: I know that you mentioned that Clara Barton never thought she was going to be a nurse or that she was going to have somewhat of a significant impact in the medical field, but where did she or how she obtain her medical training and learn her nursing skills?

Jake: When she was a child her brother was severely injured in an accident at their house and the local doctor believed that it was going to be a fatal injury. Barton, who I believe was nine at the time, stood by and she basically nursed him back to health as a child by just tending to his every need and being a comfort to him. When the Civil War breaks out, that is the only nursing experience she has, so she doesn't have any formal training. In fact, there wasn't a system to formally train nurses. That wasn't something that was present in the United States, in part because hospitals did not exist as we know them today. That system would be created out of the Civil War, just as modern American nursing is born out of the Civil War. The first trained nurses in the United States will be trained during the Civil War, outside of religious orders. I will mention that there is some crude nursing training for some Catholic nuns that served during the Civil War. That's something that goes back to I believe the 17th and 18th century in the United States and especially in Europe, so the first secular nursing training is really going to be done during the Civil War. But Barton never participates in that and she never gets formal nursing training. I had a fascinating conversation about this while working on a Clara Barton documentary project that the Red Cross is a part of. Their historian wants to make clear that the Red Cross does not recognize Clara Barton as a nurse because she never received formal nursing training. Even though she was doing some of the jobs that we would recognize today as nursing and even during the Civil War were considered similar to the role of a nurse, they don't formally recognize her as such because she never received any specialized training. She has a natural ability to do it. She has this kind nurturing personality type that actually comes out in her teaching. I always say on tours of the museum when I talk about her role as an educator. I say that Barton rides the fine line between a kind nurturing angel and a firm hard New England authoritarian. This makes her a great teacher because she can be the students favorite as she can be kind and caring but she can also mean, to put it bluntly, and get stuff done.

Sonali: While nursing soldiers back to health, Clara Barton also took it upon herself to search for missing Union soldiers. What made her want to begin this journey of finding missing soldiers and what was this process like at the time?

Memorial to the “untiring devotion of Clara Barton” at the Andersonville National Historic Site in Georgia, at the site of former Confederate prison-of-war-camp Andersonville Prison. Andersonville was Barton’s inspiration for starting the Missing Soldiers Office.

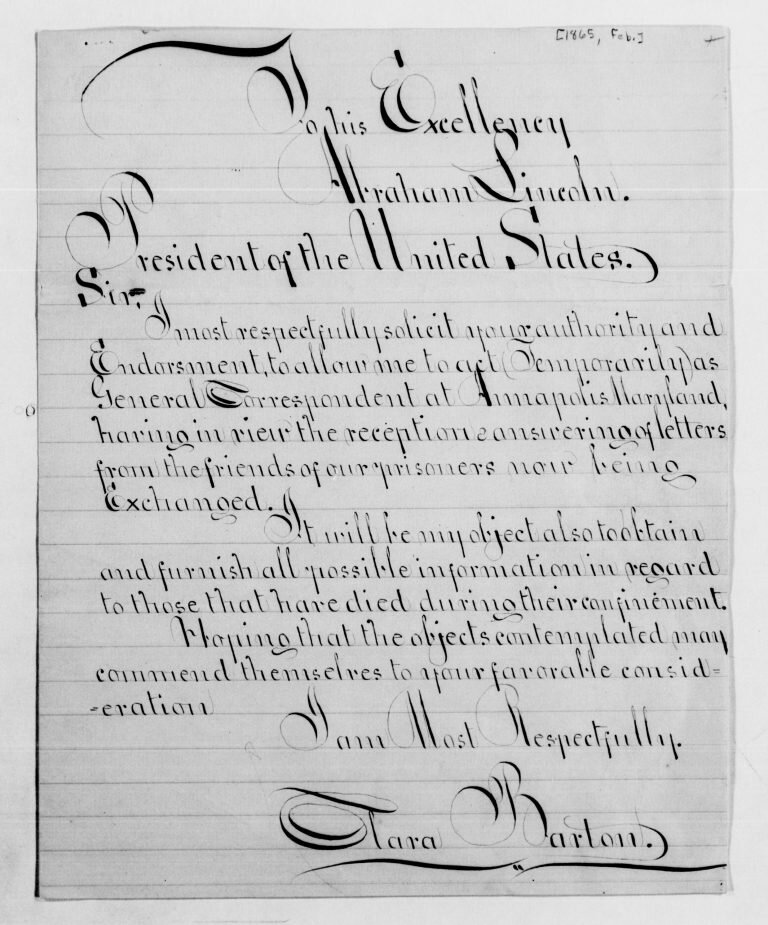

Jake: She really starts a whole movement and a kind of ideology around caring for service members who don't come home. So, in the aftermath of the war and even as the war is drawing to a close, Barton's role as a relief worker and humanitarian becomes largely obsolete as the army and the larger relief organizations have gotten really good at their job by this time. They're doing amazing work and are very well organized. As a result, Barton starts to get depressed. She starts looking for other things to do and other ways that she can support the war effort. She is very much interested in the Union cause, but she’s only focusing her work on Northern soldiers and so she learns while in Annapolis, Maryland in February 1865 about a prison camp in the South. It’s this prison camp in Georgia called Andersonville and she is horrified by the appearance of the soldiers who are being brought out of that camp and back into Union lines. They are skeletons, human skeletons and many of them died as a result of malnutrition. Disease was also rampant, and the camp was massively overcrowded. She was also horrified by the stories they told. The stories included how 13,000 soldiers held in that camp died in less than a year's time. She recognized immediately that this is a tragedy and a horror. In fact, it would go on to be the only war crime of the Civil War that someone would get convicted of. But she also recognized that it was a horror for all of these soldiers’ families who would have no idea of what happened to their loved ones. They've simply gone into this camp in the south and disappeared forever. Thus, she got motivated because of these prison camps, not only in Andersonville, but there were others, to start to try to communicate with these families about what happened to their loved ones. This was not a recognized part of the federal government, this was not the job of War Department or even of state organizations. Therefore, there is this void where no part of the government and no other agency is doing this work and she steps in to fill this need. Doing so will connect her with Abraham Lincoln, who gives approval for the office, and then Andrew Johnson, the next president, will also give approval. She gets 15,000 dollars from Congress in 1866 to really ramp this work up. That ultimately is how the Missing Soldiers Office is born. Three years of effort go into finding and recovering as many of these missing soldiers as possible. She does this work that no one else had even really thought of doing in such an organized fashion. On an individual basis this kind of thing took place at the behest of families looking for their own loved ones. However, she took this effort on and become a surrogate for all of these families to go and find their loved ones and tell them, if she could, what happened to them.

Sonali: We discussed how the Missing Soldiers Office is related to her work, but how has the Missing Soldiers Office continued this work into the present day?

The letter that Clara Barton wrote to President Lincoln asking for permission to become an official government correspondent tasked with finding the soldiers who had gone missing during the Civil War. Learn more about Barton’s work on the Missing Soldiers Office at the museum’s website!

Jake: It's one of the fascinating things that I've learned through my work at the Missing Soldiers Office Museum. Barton does 3 years of this work. She finds 22,000 missing soldiers, receives 63,000 letters from families. That's about a hundred letters a day that came into her office. Yet, she closes up the office in 1868 and basically never looks back. She moves to Europe starts the path towards the Red Cross and her work at the missing soldiers office is kind of forgotten in most parts of America. Even when it comes to Barton, her work with the Missing Soldiers Office is very much overshadowed by what she does with the American Red Cross. There are some, especially within the US Army, who look back at the Civil War as kind of a horror show because there was no effort to do really organized grave registration, identification of the dead. As a result, in the Spanish-American War of 1898, there are some of the first efforts to fix this by using the principles and ideals that Barton. Those ideals being that every American Soldier should have the dignity of having a proper burial, if possible. It really takes off in WWI with dog tags and grave registration units becoming more and more refined through the 20th century. However, when you get to Korea and Vietnam, conflicts that we don't flat out win, suddenly we have to deal with foreign governments. We're still dealing with North Korea and repatriating American soldiers from the Korean conflict. In Vietnam, that is something that we've been working on for decades since we opened: diplomatic relations with the Vietnamese government. This effort still goes on today through a federal agency known as the DPAA or the Defense POWMIA Accounting Agency. We have worked with them over the years and they look back to Barton as their inspiration. There's a direct line between what Barton did and what work goes on at the Department of Defense today. They make that connection as well and trace their origins to what Barton did during the Civil War. She really created this ideal that, when we have people in the service, that they have the right to a proper burial and it is our mission to give them that if they should meet their death in the line of duty.

Sonali: Moving on to her work with the Red Cross, Clara Barton is responsible for starting the American Red Cross and this organization still aids people across the world to this day. What made her want to start this organization? How did this come to be and what was her purpose or goal for the American Red Cross?

A commemorative postage stamp for Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross

Jake: So she does not know about the Red Cross when it is founded. The Red Cross is founded in Switzerland in 1864 as a result of a Swiss traveling salesman witnessing a horrible 1859 battle in Italy. That inspired him to create this non-partisan, non-government organization that would go between the lines to care for those in need during wartime. Europe had a lot of wars in the mid-nineteenth century, so that organization gets its official start in 1864 when it actually comes into existence and really is starting to do work. The United States is asked to attend the convention in Geneva that organizes that institution, but the Lincoln administration responds to Europe by essentially saying: we will stay in our hemisphere and you can stay in yours. Thus, they don't do anything with the Red Cross. Barton arrives in Switzerland in 1869, after years of working in the Civil War. In the aftermath of the Missing Soldiers Office, she needs a break or vacation, so she stays with a friend of hers who had worked in the Missing Soldiers Office. His family lived near Geneva. When she arrived in Switzerland, representatives from the Red Cross ended up seeking her out. They get together and she learns about the organization. It’s an epiphany moment for her because she did all of this work in the Civil War and she recognizes that an organization like this, an international organization, would have been incredibly valuable during the Civil War. So she throws herself fully into this. It’s her next mission that appears to her, so she throws herself into creating an American chapter of the Red Cross. This proves to be incredibly difficult and it takes her a decade to really accomplish this. This is where she gets really depressed in the 1870s. She gets back to the United States and it is not going well trying to raise awareness. She is trying to lobby the government in order to become a part of this international institution and create an American Red Cross. Then, when she does finally maneuver the levers of power to make it happen, she becomes its first president. For 22 years, she is at the helm of the American Red Cross and changes what the Red Cross does. She takes it out of just war time relief and brings it over into civilian disaster response: floods, fires, tornadoes, earthquakes, and not just war zone work. That is her legacy with the Red Cross in addition to traveling across the world to do this sort of work: bringing food, medical supplies, organizing emergency hospitals, utilizing triage and first aid. All of these are the efforts that Barton really brings to the Red Cross. I will say the Red Cross that Barton knew is very different from the Red Cross we have today. I don't want to call it a cult, but it was kind of a cult of personality around Barton. She had a very close clique of people that she worked with. So, Clara Barton herself and then this small group of people would respond to all of these disasters. It's not until after Barton leaves the organization in the early 20th century, where the modern Red Cross really is born. The idea of Red Cross chapters in this city or that town arises after her departure from the organization and it becomes a much more decentralized organization than it was under Barton's time.

Sonali: Are there any interesting or unknown stories about Clara Barton that more people should know about or anything that you find interesting?

Clara Barton photographed by James E. Purdy in 1904, in the last decade of her life

Jake: There is a lot. I work most closely with her time in the Missing Soldiers Office and when she lived in the boarding house, so from 1861 to 1868 is my specialty with Barton. I’m less knowledgeable about her pre-war life, her post war life and time in the Red Cross time as my area is pretty narrowly focused. But, I do have a few stories that I really like to talk about and that I would want more people to know about. One is her time in South Carolina in 1863. There's a great blog post on the museum's website about this written by one of my favorite historians, Dr. Chandra Manning at Georgetown University. This blog post talks about Barton's time working with the free population during the smallpox epidemic in Union controlled South Carolina. When people talk about Barton’s time in South Carolina, if they're really knowledgeable about Barton, they tend to know two things: one is that she nurses the wounded from the Battle of Fort Wagner, which features in the movie Glory, or that she has a pretty passionate affair with a married, white officer of a unit in South Carolina. Those are the two things that most people talk about. Of course, there are the stories of her working with these refugee populations who are basically being left to their own devices by the government, even though they are living within camps that are being managed by the federal government. Barton steps in to fill this gap as she has done throughout the war. The other story that I really love to talk about and I think in part it's because I do a lot of public history work, but Barton was a prolific member of numerous speaking tours. She traveled across the North starting in 1865 to 1867 speaking about her Civil War service and what the Missing Soldiers Office was trying to accomplish as a way to raise money for the office. The Library of Congress has digitized her collection of speeches and I encourage people to go to the Library of Congress and read through these documents. It is amazing. They are working on transcription in addition to having them digitized now, but there are her full speech notes that are included that you can actually go read. I did this kind of surveying of newspaper archives to see in all of these little towns she stopped in where she spoke and how they wrote about what she said. But then to be able to go to the Library of Congress and read the actual speech is just awesome. You can kind of visualize her up on the stage speaking and it's amazing you can kind of see when she is not on on top of her game or has a bad night. You can see when she might be feeling a little sick and you can read about this in her diary, which is also preserved, so there's so much information about her in this time and what she was experiencing. It is just an amazing part of her life. Her role as a prominent public speaker and public figure and I think that is lost in the shuffle when we talked about her work as a nurse or “not a nurse”, humanitarian, and administrator in the Missing Soldiers Office. She also has this fundraising and speaking role. Then again I think it's because I do this sort of work on the Missing Soldiers Office Museum’s behalf, that I find it fascinating to be able to go and read how she was trying to raise money for this very same place.

Sonali: My last question, I know that we discussed her life and her legacy as a nurse or “not a nurse”, as a humanitarian, as this public speaker and person that has been fundraising for her organization. Is there anything else that her life or legacy has continued on in or that she has changed or been apart of that not that many people know of?

Jose Andres (far right) and his World Central Kitchen team working to feed National Guard troops on site after the events of January 6, 2021. Photo from Rep. Andy Kim’s (D-NJ 3rd District) Twitter account. You may view his thread about Andres and World Central Kitchen at the Capitol here!

Jake: There's a connection that I find fascinating. The museum is across the street from Jaleo, which is one of the great restaurants here in Downtown DC. It is owned and managed by Jose Andres, who has become quite the public figure in recent years for advocacy on numerous fronts. He started this organization, World Central Kitchen, and does amazing work in Puerto Rico as well as all across the country and around the world. He credits Clara Barton and her work as an inspiration for him. He’s explained this on a couple occasions publicly about how his restaurant was across the street the site for our museum was rediscovered to be Barton’s original Missing Soldiers Office in 1996. He learned about Clara Barton as a result of that discovery and found these amazing parallels. Those parallels continue to deepen and those connections get weirder over time, I will say, in ways I would have never thought imaginable, so he is a direct legacy of Barton. His work is directly tied. He's doing the same kind of thing by feeding those who are in need, one of the crucial roles that Clara Barton fulfilled during her time. Where it gets downright weird for Jose Andres is that in the aftermath of the events of January 6th here in Washington, his organization went and fed many of the National Guard members who came to defend the Capitol Building. What even Chef Andres didn’t realize is that Clara Barton did the same thing a hundred and sixty years earlier and that had been her inspiration to start the work in the Civil War. Therefore, there's this weird parallel between what Clara Barton did and her inspiration to get involved in relief work and in humanitarian work and how, 160 years later in the same place under weirdly similar circumstances, Jose Andres is continuing that work and that legacy. I don't know whether or not he knew of that connection when he was doing that work, but it's kind of an eerie parallel. The fact that the restaurant is literally across the street from where Barton lived and where he got his start, but it's a fascinating connection and we are looking forward to finding ways to draw upon those connections. Talking about Chef Andres is one of them, but there are millions of other people who are continuing Clara Barton’s legacy: whether they are doing so knowingly or are just filling this humanitarian desire that Barton exhibited throughout her life.

Learn More

Visit the websites of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum

Follow the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum on Instagram

See more of Jake Wynn’s work on his website, Wynning History