Tout le Sang Coule Rouge: The Story of Eugene Bullard

Today’s entry is a special guest post by our friend & tour guiding colleague Larry Clark of Federal City Tours!

With a nod to Madame de Boineville (my high school French teacher), I should probably explain the title of this post. “Tout le sang coule rouge” is not from the clever mind of some Hollywood scriptwriter. It is the actual title of an unpublished autobiography of, oddly enough, an American. The story of Eugene Bullard is one of grit and determination and should have been taught in schools, but wasn’t. His inspirational life should have been the subject of a major Hollywood movie, but wasn’t. The truth is, his story couldn’t be told in just 2 ½ hours. I can only hope someone from Netflix reads this! “Tout le sang coule rouge” translated means: “All blood runs red” and while most of Bullard’s story takes place in France, he is a genuine American hero.

Eugene Jacques Bullard, born Eugene James Bullard, in his military uniform during World War I

Yet, you’ve never heard of him? Bullard was forced to pursue greatness on foreign shores simply because of his race. His real life story was so improbable that publishers of the day thought his autobiography was complete fiction. After all, how could a 12 year old Black kid from rural Georgia with a 5th grade education run away from home, become a winning jockey (which paid his way to Europe), go on to become a vaudeville performer, prize fighter, jazz musician, night club impresario, highly decorated soldier (for the French Foreign Legion) in two World Wars AND was a spy master extraordinaire? But his crowning achievement is certainly being recognized as the first African-American combat fighter pilot. Publishers said, “Nah, no way!”... But, it’s all true!

Eugene James Bullard (Gene for short) was born on October 9, 1895 in Columbus, GA. Gene was the 7th of 10 children to William Bullard, a formerly enslaved person and his wife, Josephine, a member of the Creek Indian nation. Father William was born in the French colony of Martinique and Gene’s grandfather was born in Haiti (also French). Young Gene grew up in the segregated South. Although half Creek Indian, Gene would embrace his father’s family oral tradition and mystical connection to France. While surrounded by racial prejudices in the US, it is understandable that William would regale his children with the virtues of a color-blind France. He explained that in France (much like with the Creek Indians) if you worked hard, the color of your skin didn’t matter. Gene soaked in the idea of this racial utopia somewhere across the ocean. It would shape his world view and eventually, his destiny.

Soon, a series of events would change his life: In 1902, his mother, Jossie, tragically died in childbirth. Just two years later, his father was involved in a racially motivated altercation with a white man at work - his supervisor, no less. Even though the supervisor initiated the assault, the danger of a Black man striking a white man – justified or not – could have deadly results. In light of the expected reprisal, William prepared his seven young children for his likely lynching. Thankfully a timely intercession by the white company owner prevented William’s murder. But the ever-present threat of lynching so shook young Gene that he determined to run away from home and find his way to that racial utopia his father had spoken of: France. He was only nine years old.

Between the ages of 9-11, Gene made several attempts to escape. By the time he was 12, he sold his cherished goat and cart, finally giving him the means to strike out on his own. The next 5 years are not well documented, but everything he did was part of his grand plan to escape across the ocean. Aided by a quick wit and a ready smile, Gene found work and made friends easily. He eventually found himself in the port of Norfolk, VA. The size of the ships told him he was in the right place – surely one of them was going to France!

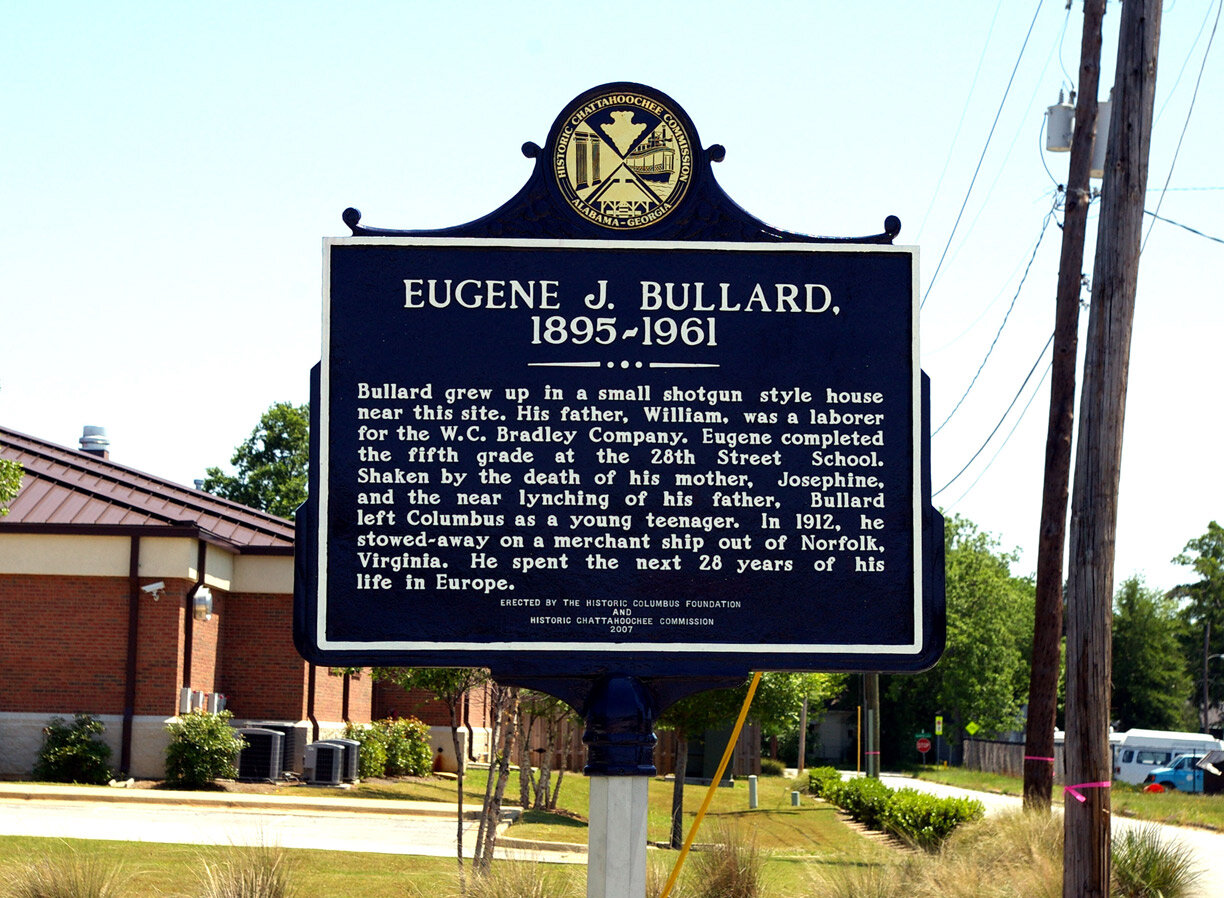

Historic marker near the site of Gene’s childhood home

In March of 1912, Gene snuck aboard a German ship, hiding in a covered lifeboat. After 3 days, Gene climbed out of his compartment and startled a crew mate who promptly turned him over to the ship’s captain. The skipper was furious with the stow away. Completely within his maritime rights, the captain threatened to toss the young man overboard, but Bullard pleaded: “The fish have plenty to eat without me!” and this made the captain laugh. Bullard’s charm and promise to work hard earned him a place on the crew. During the crossing, Gene picked up a passable understanding of German, which proved invaluable to him, later in life.

At their first port of call (per maritime law) the ship unloaded the stow away in Aberdeen, Scotland. Gene quickly found the Scottish version of English more difficult to learn than German! Sadly, he realized France was still a thousand miles away and he would have to cross another body of water to get there. Bullard worked his way to Glasgow, then to Liverpool, England – one of the world’s great seaports and home to the tragic RMS Titanic which had left on its fateful journey five months earlier.

In Liverpool, he found work as a longshoreman. During this time he also began to physically mature. He eventually stumbled across Baldwin’s Gym, where he discovered boxing. A year after leaving the United States, and with only a few months of training in the ‘Sweet Science’, Gene found himself on a professional boxing card that featured the popular Alan Lister Brown, aka The Dixie Kid. Gene fought as a Welterweight (147lbs), telling his trainer he would “fly around the ring” so as to avoid direct shots, a tactic which earned him the nickname The Sparrow.

Gene as a young boxer

To understand, boxing in Europe during this time was as popular as soccer is today. Skilled boxers were hot commodities and Brown immediately recognized Gene’s raw talent; The Sparrow won his first fight. The Dixie Kid invited Gene to join his company of fighters and three days later, he soon moved to London. There, Gene’s natural ability as an entertainer was soon discovered. Gene began performing in Ms. Belle Davis’ Freedman’s Pickaninies, a slapstick/ Vaudeville review. When not in the ring, he was on stage, singing & dancing. These gigs supplemented his boxing income and he found himself touring Europe with the troupe. He toured with The Kid and then alternately, toured with Ms. Belle. After finishing a tour with The Picks, he decided to stay in Paris. In the spring of 1914, Bullard finally made The City of Light his home. Old boxing connections helped him land odd jobs, including interpreting for other African-American boxers - the controversial Jack Johnson among them. Little did anyone know that by the end of that summer the whole world would change.

By the time the ripple effects of Archduke Ferdinand’s assassination hit France, the world had plunged into war. A wide-eyed 19 year old wanted to defend his newly adopted country, so Gene volunteered with the French Foreign Legion. Assigned as a machine gunner to the 1st Moroccan Division and later, the 170th French Infantry Regiment, Bullard’s unit saw significant combat, earning their nickname: The Swallows of Death. Bullard was severely wounded in the trenches of Verdun. During his painful recuperation, Bullard was classified “no longer fit” for trench combat. However, his serious leg injury would not exclude him from work as an aerial machine gunner. As the advantages of aircraft were rapidly becoming apparent, volunteers were needed. Bullard leapt at the chance to continue his service to France.

Bullard transferred to aviation school in October of 1916, but only as a gunner - the color barrier for pilots had not been broken. He also heard of a squadron made up exclusively of Americans, called the Lafayette Escadrille and immediately requested a transfer. He was denied solely based on the color of his skin. Despite the indignity of being turned down by fellow Americans, Bullard persevered. In mid 1917, with the help of Jean Navarre, France’s 1st flying ace, Eugene “Jacques” Bullard passed his flight tests and was awarded pilot #6950 in the French Air Service – officially becoming the first ever African-American pilot. At the time, news of this momentous occasion was deemed a “security threat” at home and was suppressed by Woodrow Wilson’s intolerant administration.

Since the life-expectancy of a WWI pilot was short, aircraft were generally not painted, unless the pilot had achieved success, like the Red Baron. Bullard’s aircraft had a visual message as his chosen insignia. A later biography describes how Bullard distinguished himself:

“He always flew with a large red heart, painted each side of his fuselage, right behind the cockpit. The heart bled, pierced by a dagger. Above the heart was stenciled the following: Tout le sang qui coule est rouge – in English, All Blood That Flows Is Red… It was a powerful slogan, one he adored. ”

As mentioned earlier, a slightly modified version of this statement became the title of his unpublished autobiography.

During his three month stint with the French Air Service, Bullard flew about 25 combat missions and shot down 2 enemy aircraft, although not confirmed. By Armistice Day in 1918, Eugene “Jacques” Bullard had amassed a dozen medals and citations from a grateful nation. Among the highest awards: the Légion d'Honneur & Médaille Militaire, bestowed for conspicuous courage in the field. Two Croix de Guerre, each, a citation for gallantry, above and beyond the call of duty. Not bad for the son of a formerly enslaved man slave, huh?

The medals of Eugene Bullard on display at the U.S. Air Force Museum

After the war, he went home to Paris and returned to what he knew. As before, he worked at a gym, sparring with up-and-coming boxers. But the intoxicating nature of Jazz music began sweeping over post-war Paris, as nightclubs were popping up all over the city. Jazz was like nothing anyone had ever heard. It made Parisians feel good and helped them forget the horrors of war. If you could sing or play an instrument, there was work. So he quickly became a competent jazz drummer. He befriended a successful club owner named Joe Zelli whose Club Zelli would become the epicenter of the expanding Jazz scene in Paris. Zelli hired Gene to book the musical acts and in short order, he would have his finger on the city’s entertainment pulse. After establishing Club Zelli as THE place in town, Bullard went out on his own, first managing Le Grand Duc, then buying it four years later. His new business partner was a Jazz singer and dancer from Chicago, known for her shock of red hair: Ada “Bricktop” Smith who had worked in Jack Johnson’s club, Le Champion, in the states. Bullard also hired a dishwasher/busboy named Langston Hughes. Bricktop soon invited others in her orbit, like Josephine Baker. The club’s clientele served as the roll call for the Jazz Age: Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Cole Porter, Mable Mercer, F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Noel Coward, James Joyce, Gloria Swanson, Fred Astaire, Fatty Arbuckle, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Edward Windsor, the Prince of Wales and bandleader, Arthur Dooley Wilson – who would become immortalized in the film Casablanca, as the club’s piano player, Sam. Another patron was a former wartime ambulance driver, named Earnest Hemingway. Hemingway would base a character off Bullard in his 1926 masterpiece, “The Sun Also Rises”.

The 1929 Stock Market crash threw a wet blanket on the decade long, never-ending party. Although it was not an ideal time to open a new club, Bullard never shied away from a challenge and in 1931, he opened Club L'Escadrille. One by one, the other Jazz clubs of Paris began to close down, but with the help of his old friend, ‘Satchmo’ (short for satchel mouth) Louie Armstrong, Club L'Escadrille flourished. As early as 1934, Bullard began to notice the influx of Germans into Paris, following Hitler’s ascension to power. The Germans – specifically Nazis – frequented Bullard’s club and spoke freely, assuming the Black guy was just an ignorant American bus boy. Bullard agreed to spy on the Nazis for the French government. In the late summer of 1939, he passed on intelligence indicating the Nazis would attack Poland and not Belgium, as expected. This valuable intel was ignored and on September 1, 1939, World War II began with Germany invading Poland – just as Bullard said. When the Nazis invaded France eight months later, he closed "Club L'Escadrille" and at age 44, volunteered with the 51st Infantry Regiment. He was severely wounded at the Battle of Orleans in June of 1940. Days after France surrendered, Gene would hobble 500 miles to the Port of Bilbao in Spain, then on to Lisbon, Portugal, where he caught a steamer bound for New York. The country that did not want him had now become his lifeboat.

Once in New York, he recuperated at a hospital. The disappointment of never fully recovering from war wounds was compounded by the crushing blow of no longer enjoying the celebrity that he had achieved in France. He did what he could and was successfully sold French perfume on Park Avenue. In the late 1950s he became an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center - the headquarters of NBC. He would always wear the medals bestowed by his adopted country on his neatly pressed uniform, serving as a conversation piece for anyone interested.

The statue of Eugene Bullard at the Museum of Aviation just outside of Robins Air Force Base

In late October, 1959 former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt recognized Gene in her column “My Day” after he was awarded France’s highest honor, the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur. Just before Christmas that same year, Dave Garroway, host of NBC’s The Today Show, noticed the new medal on Gene’s uniform (although Garroway always engaged in polite chit chat, he had never truly seen Eugene Bullard until this moment). When he learned the story behind the award, he pressed Gene to appear on air. Gene agreed, requesting that he be allowed to wear his prized elevator operator uniform. On December 22, 1959, the story of Eugene Bullard, the first African-American fighter pilot, was seen by 4 million people. While NBC got a positive reaction, Gene’s story soon receded, like waves on the beach. Eugene Bullard died in 1962 at the age of 66.

In 2019, Georgia’s Warner-Robins Air Force Base installed a statue to their local hero, Eugene James Bullard - The Sparrow. Now you know his story. I’m sure his mother & father would be proud.

About the Author: Over the years, Larry Clark has built a solid reputation for fun, engaging and historically accurate tours. Now in his third decade of sharing his passion, Larry has entertained well over 100,000 guests with his highly acclaimed storytelling tours of DC, as well as the surrounding DMV area. You can learn more about him and his fellow tour guides at Federal City Private Tours. Check out their tour catalog here!

You can follow Federal City Private Tours on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook as well!